This website uses cookies

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you continue to use this site we will assume that you are happy with it.

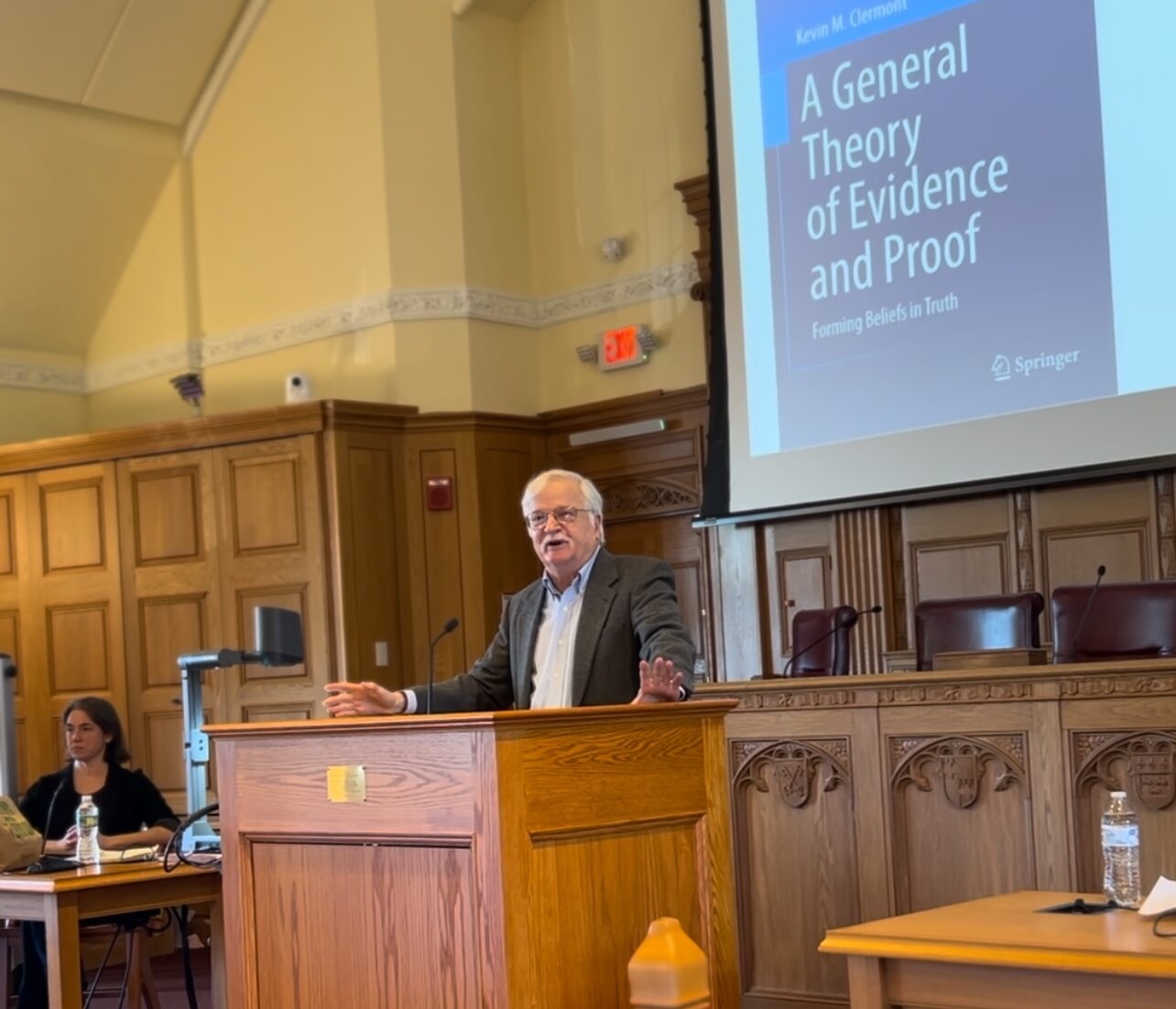

In the fall, Cornell Law School celebrated the release of Kevin Clermont’s new book, A General Theory of Evidence and Proof: Forming Beliefs in Truth. The book celebration, held in the MacDonald Moot Court Room, featured comments from Clermont, Robert D. Ziff Professor of Law, and Cornell Law colleagues Michael Dorf, Robert S. Stevens Professor of Law, and George Hay, Charles Frank Reavis Sr. Professor of Law.

As Clermont explained, his book addresses the time-honored debate over how humans analyze the pursuit of truth. The question the book attempts to answer, he noted, is “Should you proceed by belief or by probability?” Tracing probability’s later origins to 17th-century mathematicians Pascal and Fermat, Clermont highlighted its evolution from supplanting belief analysis in education to its influence in law. While lawyers have contributed to probability’s development, courts still grapple with finding facts by “inner convictions of truth,” he noted. The essential message of his book is that law has crafted a sound model of non-additive, multivalent beliefs, tailored to its needs and methods.

“The book has two main claims that are remarkable in their juxtaposition,” said George Hay. “The first is that law scholars who write about evidence, or at least some of the more prominent ones, have been using probability, where it really doesn’t fit . . . . But the second claim that Kevin makes, which is supposed to help us sleep better at night, is that on the ground, judges and juries actually get it right most of the time. It’s the academics who are confused.”

“Kevin lifted the veil from my eyes and made me realize, no, it is possible to think that what the law is doing actually makes sense and is just, and that the problem is probability’s product rule,” said Michael Dorf.

The big takeaways from Clermont’s book are that, “the intuitive approach to evidential proof, which prevailed before Pascal, makes theoretical sense after all.” Clermont stressed that “the standard of proof can be applied to each element or to the party’s whole case, yet it works out the same. Inferences can be cascaded upon inferences without invoking the product rule.” When applying this to everyday life, Clermont said to trust belief functions as they pertain to factfinding, law, and science as well.

Clermont is one of the leading experts on civil procedure in the United States, and this is his second book in two years. Clermont also celebrated the launch of the George Washington Fields autobiography, “Come on, Children: The Autobiography of George Washington Fields” back in February — a book he edited.